The Forgotten ’66

by Bottom Dealin’ Mike

U.S. Scout blasts away with the revolving carbine

Bottom Dealin’ Mike squinted into a churning cloud of dust and smoke at the shrieking horde of mounted men thundering by the makeshift corral. Beside him he could hear poor Hollister choking in his own blood. Each labored gasp was a bubbly wheeze that took him one breath closer to his final reward. Whether his soul traveled up or down was between Hollister and his maker, but the Herald man was certain either direction was better than this Hell on the Big Horn. As a reporter for the New York Herald Mike thought a short trip up the Big Horn to visit the contract hay cutters might provide some him with something more interesting to write about than the tedious post routine at Fort C. F. Smith. But being attacked by half the Sioux nation was a more interesting situation than he’d had in mind. The Herald man rested the barrel of his Remington revolving rifle on the splintered foundation log of the corral and fired his last round into the churning juggernaut of native cavalry. He saw two riders separate from the troop and charge straight towards him. Cursing his luck, he dropped the empty rifle and leapt to his feet. He drew his Remington New Model Army revolver, firing as he rose. But his feet slid out from under him in the slippery ooze of Hollister’s blood. He landed hard on his rump just as a lance flashed through the air where his chest had been a moment before. The pistol was jarred from his hand, but he snatched up Hollister’s Winchester Yellowboy and started firing. He put two rounds into a horse and the third into its rider as he jumped free. Then he heard little dry clicks as he jacked the lever and pulled the trigger on an empty gun. The Herald man dropped to his knees, wrestling with the dead weight of Hollister’s body to free his cartridge belt.

"They’re pulling back," Al Colvin called. "How do we stand?"

"Hollister’s dead," the reporter called back over his shoulder.

"So’s Sternberg," one of the hay cutters said.

While sliding .44 Henry rounds into the loading gate of the ’66 Winchester, the correspondent looked over towards the opening in the corral. He watched two troopers from G Company pull Lt. Sternberg’s body to the side of the corral. A thin trail of blood from his shattered skull marked their passage like a line drawn on a map. The reporter tried to feel sorrow for the lieutenant, but the truth was that pig-headedness and misplaced pride had killed Sternberg as much as a Sioux bullet. Sternberg insisted on standing in the corral opening and,"Fighting like a man," as he put it. If Sternberg had even a lick of sense, he’d still be alive. He felt more pity for Hollister who just didn’t jump for cover fast enough.

"Are you taking Hollister’s rifle?"

The reporter looked up at Al Colvin, the head of the contract hay cutters. The big man was standing over him scowling. The reporter turned to the corpse lying in a bloody pool beside him. "Hey Hollister…you mind if I borrow your gun?" he asked loudly. He waited for a moment, letting the silence hang in the air.

"I don’t think he cares Colvin," the reporter finally remarked in an even voice. "What’s it to you?"

"Just askin’ is all," Colvin replied. "I guess you changed your mind about that Remington of yours?"

"I guess I did," the reporter answered.

The night before they’d sat around the campfire eating beans cooked with bear ribs and sipping whiskey. The conversation had turned to guns. They’d talked about the new .50-70 trapdoors issued to the troopers that week, and about the Winchesters carried by the civilian hay cutters. The reporter had defended his choice of a cap and ball, revolving rifle against the good-natured ribbing of the men around the fire. He’d learned a lot in one day.

"I guess you ain’t as dumb as I thought," Colvin remarked with a twisted grin. "Anyway, if you ain’t using that Remington, I’d appreciate it if you’d let Zeke use it. He ain’t as smart as you yet, so I reckon it’ll do him fine."

"I reckon a kick in the pants will do you fine too," Zeke said hotly. He was ramming a minnie ball down the bore of his Enfield. "I don’t need no repeater," he said. "I been carrying this rifle since Shiloh."

Zeke capped the nipple. "Heck Al, I got the first injun of the day with this old girl."

"Yeah and you spent the rest of the day reloading her," Al shot back. "What are you gonna do if they get through that wall Zeke?" he demanded, "throw rocks at ‘em?"

Al flashed a wicked grin. "Maybe you were thinking of blowing kisses at them, eh?" he said. "Make ‘em think you’re a winkteh."

"Just give me the danged Remington and rest your jaw," Zeke snapped. "He won’t never shut up unless I do what he wants." He said to Mike.

Mike handed Zeke the revolving rifle. "It loads like a belt pistol," the Herald man explained.

"No kidding?" Zeke said sarcastically. "Maybe you can explain how my fly buttons work next."

He sat down and started loading the rifle’s chambers with powder and ball. "As if today ain’t enough of a trial," he remarked. "Now since that milk-sucking lieutenant’s gone and got himself killed, ol’ Al thinks he’s cock of the walk."

"He’s doing pretty good so far," the Herald man said. "I’m not complaining."

"Well of course he’s doing good," Zeke said it as if he was talking to a particularly slow-witted child. "He does everything good." He crunched the powder under the last ball and turned the gun to cap the nipples.

"So what’s the problem?" the Herald man asked.

Zeke gave him a pitying, sideways look. "You must be an only child," he said.

"Close enough," Mike answered. "The others were babies when I left." He shrugged. "I’ve been gone a long time."

"Well, there you have it," Zeke said, as if that explained everything. "Al’s my older brother," he said. "It ain’t possible to like him, and it ain’t legal to kill him."

Al walked by and kicked the sole of Zeke’s boot. "Here they come again," he jerked his thumb at the wall of the corral. "Out of the north," he said. "Look sharp!"

"Lord, it’s going to be a long day," Zeke muttered under his breath.

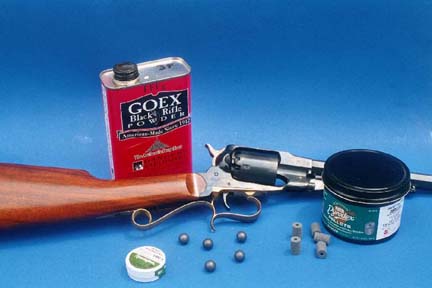

BDM uses either B-P or Pyrodex pellets in the 1866 carbine.

Remington #10 caps fit best.

Back in 1866 the folks running Remington made one of the biggest marketing blunders in the history of marketing blunders. There are people who say timing is everything. If that’s true Remington had nothing going for them in 1866 when they launched their cap and ball revolving rifle on the arms market. It was an idea whose time had clearly passed. Not only were cartridge long guns coming in to their own. To add insult to injury, that same year Winchester unveiled the improved Henry rifle. The Winchester improved Henry is of course now known as the 1866 Winchester . Nicknamed the Yellowboy because of its bronze gunmetal receiver, the ’66 Winchester simply buried the ’66 Remington. It’s easy to see why. The 1866 Winchester was a high-capacity, fast shooting, cartridge firing repeater that was easier to load than the original Henry rifle thanks to the new, side mounted loading gate. In contrast, the 1866 Remington was a six-shot cap and ball rifle. It was fast shooting, but deathly slow on reloads. Remington tried to remedy that situation by offering drop-in cartridge cylinders for their rifle in 1868, but it still wasn’t a match for the Winchester’s popularity. After 13 years of production Remington had sold less than a thousand of these rifles so they discontinued the model.

If I’d been in Bottom Dealin’ Mike’s place at the Hayfield fight, I’d have scooped up a Winchester myself. But, luckily, the Sioux aren’t likely to attack my little homestead anytime soon. So I can feel free to enjoy my Remington revolving rifle in its modern incarnation.

Uberti builds the only modern replicas of the 1866 Remington revolving rifle, and they’ve done an outstanding job of recreating these little gems. The only significant difference between the Uberti replica and the originals in the barrel length. Original ’66 Remingtons had either 24 or 28 inch tubes. Occasionally a 26-inch barrel shows up, but they were only available on special orders. Today’s replicas have an 18-inch barrel, and they are designated as Remington Revolving carbines by Uberti. Essentially these rifles use the same action as the Remington New Model Army revolver. This pistol is often erroneously called the ’58 Remington because of the 1858 patent date stamped on it, but actually calling it the ’63 Remington is more accurate. At any rate the action parts on Uberti’s replica carbines interchange with parts on their handguns. If you are familiar with cab and ball revolvers, there is little new to learn about the revolving carbine. The loading process is exactly like loading a Remington New Model Army handgun. You start by pouring a measured charge of black powder into a chamber. I’ve found that 28 to 30 grains of fffg grade Goex black powder is more accurate than the 35-grain maximum load. Then you place a .451 diameter round ball over the chamber mouth and ram it home until the powder crunches a bit. Optionally you can place a lubed felt wad between the powder and ball. I’ve personally found them to be of little value though. After loading five of the six chambers, you need to fill the chamber mouths with black powder lubricant. That will keep the fouling soft from shot to shot. This is important both for accuracy and to keep the action from gumming up. I make my lube from a mixture of beeswax and Crisco. I recommend loading only five chambers for safety, but back in the nineteenth century they’d have loaded all six and rested the hammer nose in the safety notch. So, when you’ve greased all five loaded chamber mouths, all that’s left to do is cap the nipples and fire away.

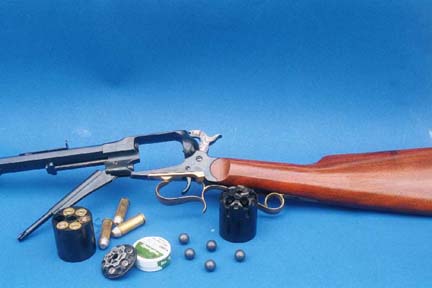

An R&D cartridge cylinder makes the revolving carbine a double threat.

Alternately, if cap and ball isn’t your cup of tea, Kenny Howell of the R&D Gun Shop makes drop-in cylinders that converts these rifles to cartridge guns. The two-piece cylinders are based on the 1868 Remington conversion cylinders except they are chambered for .45 Colt cartridges rather than .46 rimfire rounds. The same drop-in cylinders that you can buy for Uberti replica Remington pistols fit the carbines as well.

When it comes time to fire the revolving carbine, you’ll have to hold it differently than a lever gun. You should never get your hand in front of a revolver’s cylinder, especially a cap and ball cylinder. There are plenty of documented cases of people losing fingers due to multiple discharges from Colt’s cap and ball revolving rifles. Also, hot gasses coming out of the barrel cylinder gap can cut your wrist to ribbons. That’s the reason Remington designed their rifle without a forearm. You hold it with both hands back on the triggerguard. By tucking your off-elbow tight to your body, you can achieve a rock-steady hold. In fact these short rifles handle and shoot very well. I can generally shoot sub-two inch groups off-hand from 25 yards with my ’66 Remingtons. And, believe it or not, I use these little gems as my main stage rifles in cowboy action shooting. Because most stages call for more than five rifle rounds I wear two belt pouches for replacement cylinders. I fire five rounds, pull out the cylinder and put it into the empty pouch. Then I pull a loaded cylinder from the other pouch, slap it into the carbine and finish the stage. You can’t win a match like that, but the styling is awesome!

For stage use in the cap and ball mode I’ve developed a couple of tricks to speed up the loading process. Instead of loose black powder, I use pre-formed Pyrodex Pellets at matches. These are 30 grain equivalents that drop right into the chambers. After the balls are seated I cover the chamber mouths with pre-cut grease wads. I punch these out of a sheet lube using a bored out .45 Colt case. These two steps have cut my reloading time in half.

My favorite era of the old West is the decade from 1866 to 1876. I can team the Remington revolver in cap and ball mode with a pair of cap and ball sixguns. Or I can pop in the .R&D cartridge cylinders and mate it to a pair of cartridge conversion revolvers or my 1872 Open Top. Either way, the forgotten ’66 gives me a teal taste of the old frontier.